Edited by Brian Birnbaum and an update of my AMD deep dive.

1.0 AMD´s Disruption of the GPU Market is Underway

If the MI300 gains the level of traction that management is pointing to, AMD is well on its way to carving out a spot in the GPU market.

The main takeaway from Q2 is, ostensibly, that AMD is geared to ramp up its AI business over H2 FY2023. Headlines can be misleading in this sense, because the business now has many segments: the expected relative weakness of both the client and embedded segments disguise the fact that management expects the datacenter business to grow 50% in H2 FY2023, driven by AI.

Matt Ramsay: “ Last quarter, you had given us some metrics around potentially being able to grow your datacenter business by 50% in the second-half of the year versus the first-half. And maybe you could give us a little bit of an update?”

Lisa Su: “ We see very strong pull on the MI300 accelerators that are starting production in the fourth quarter. [...] And we are still looking at a zip code of, let's call it, 50% plus or minus second-half to first-half.”

Also note that the expected weakness of the embedded segment seems to be more of a relative thing, with it coming off six sensational quarters of growth in a row.

Per management's comments, the MI300 chip is attracting meaningful interest from customers. Perhaps even more important is that the MI300 is chiplet-based. If it gains half the traction that management expects it to, the MI300 signals an important milestone in AMD´s quest to disrupt the GPU space and take market share from Nvidia.

As I outlined in my AMD deep dive (which was essentially an update of my now nine-year-old AMD thesis), chiplets enable:

higher yields and,

eventually, performance tantamount to monolithic chips.

This playbook resembles deeply the one Lisa Su and AMD used to usurp Intel as the CPU market’s alpha dog.

Even though the MI300 may not outperform Nvidia´s A100, it serves as a platform from which AMD can iterate its way to higher levels of performance. Over time, and especially as we move beyond the 5nm domain, AMD’s chiplet-based products will yield more than that of the monolithic counterparts–as will performance, one day.

Below is a brief explanation.

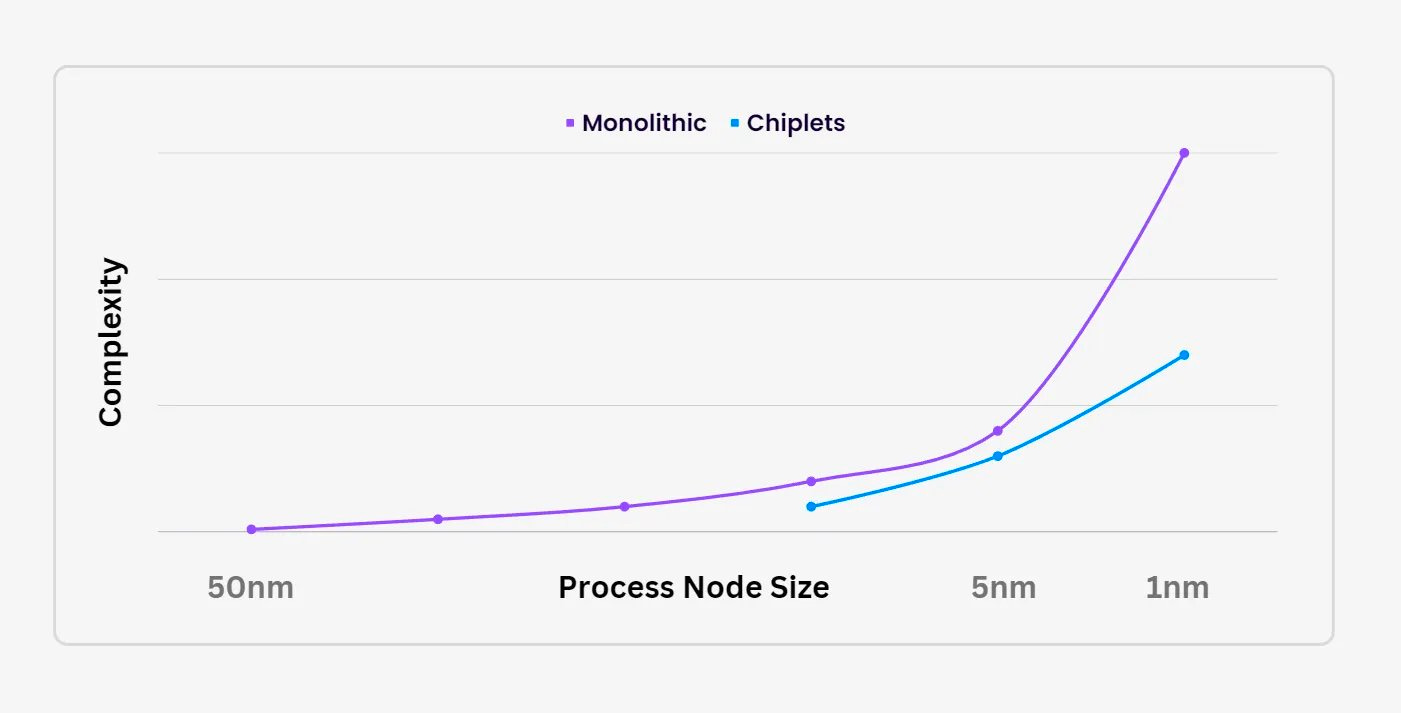

We want to make the components within chips smaller, to cram in more computation power. As the components get smaller, the chips get exponentially harder to design and make. A 5 nm process node, for example, refers to chips which have transistors that measure 5 nanometers in width.

The complexity is far easier to navigate when a chip is made of many small chips (chiplets), than when it is one big chip. This is because in the former case, if one of the chiplets goes wrong you do not have to throw the entire chip away. In the latter case, if one small component goes wrong you do have to throw the entire chip away and thus, yields are much lower.

As the components within a chip get smaller and complexity goes up, it is easier to make chips when operating on a more fault tolerant design/manufacturing platform a.k.a chiplets.

The folks at Nvidia are anything but dumb. Still, unless they pivot hard they are likely to be disrupted over the coming years.

The architecture of the MI300 has also caught my attention because of its prodigious memory. I wrote a post some months ago explaining how LLMs (large language models) will change computing over the coming decades. Essentially–and as evidenced in part by the design of the MI300–LLMs will require that memory and compute power be:

decoupled,

yet located on-chip,

and arbitrarily modifiable–in the sense that if you want more memory/compute, you can just crank them up separately without having to build a whole new architecture.

This is because LLMs are large and must be stored on-chip to minimize latency. If they are not stored on-chip–because they do not fit, for example–then information takes too long to get to the compute engine and back. As a result, the chip in question will make inferences too slowly.

Where I am going with all of this is: Nvidia has honed tech to connect chips (NVLink) and AMD has honed technology to connect components (chiplets) within chips (AMD Infinity Fabric). The latter thus has a structural advantage when it comes to bringing chips that accommodate ever heavier and more computationally demanding LLMs—which are becoming ever heavier and more computationally demanding.

Incidentally, the above architectural abstraction is likely to be relevant for whatever AI models arise over time: they will be large and therefore will need to be stored near the compute engine so inferences can be made quickly. No one will tolerate slow inferences, just like today no one tolerates a slow internet connection.

2.0 Financials

The company is in good financial health to tackle the AI opportunity from here.

I do not like to see the client and gaming segments continue to decline (revenue is down 54% and 4% YoY, respectively), but the dynamic does fit the overall macro environment. Consumers have pulled back on their purchase of tech devices over the last year and AMD is not exempt.

However, the balance sheet remains very strong, which affords the company plenty of powder to make investments in the future:

Cash and equivalents came in at $6,285B.

Debt came in at just $2,467B.

Further, the company's strategic priority to invest and become a dominant player in the AI space is the correct one. Success in this endeavor will lead to far more attractive financials in the future.

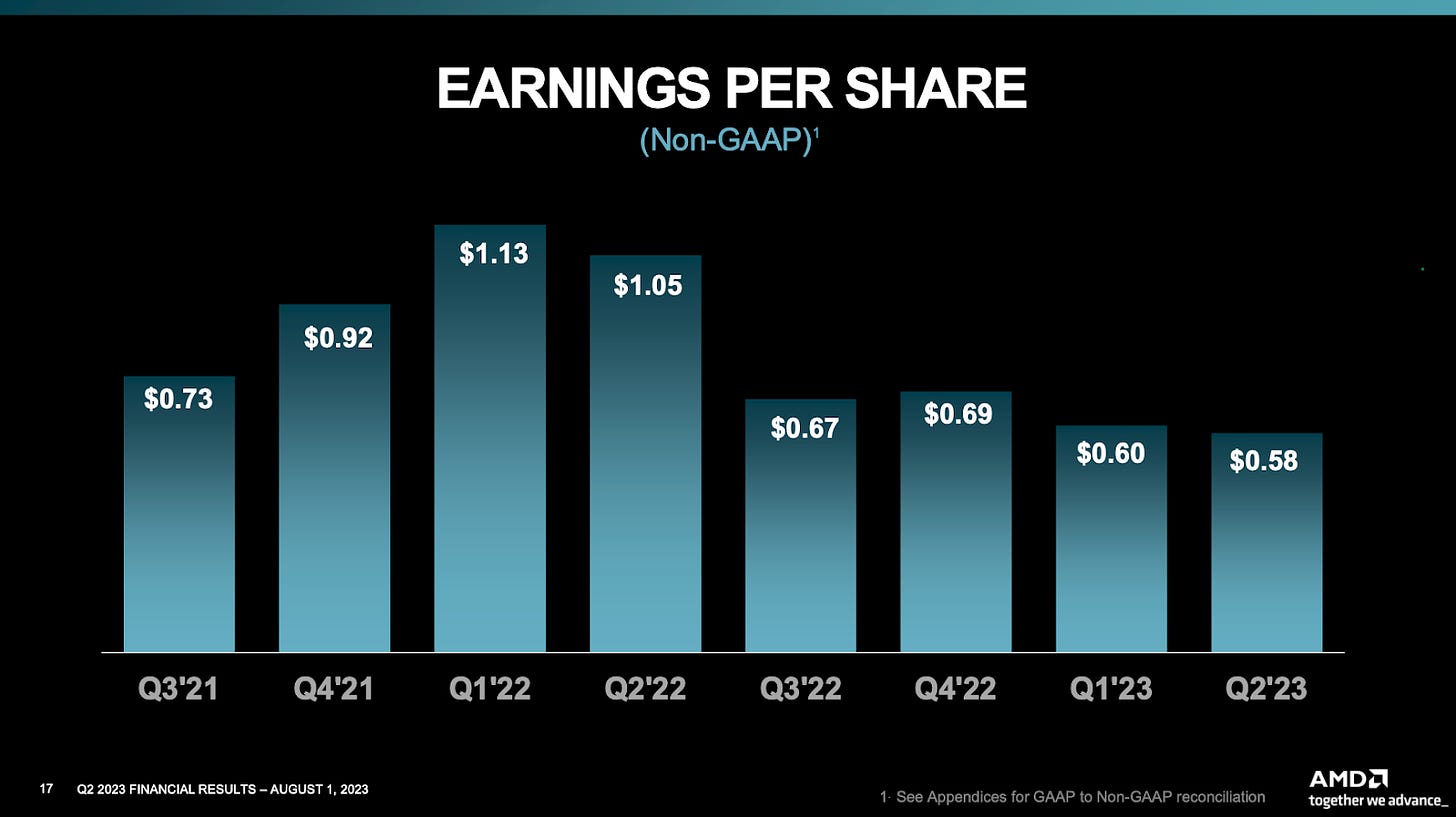

Additionally, for those of you that are new to the company, bear in mind that AMD´s GAAP financials include the amortization expenses of the Xilinx acquisition. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) dictate that the cost of purchasing a business be amortized over time. Since amortization isn’t a cash charge, companies often include non-GAAP income statements, which depict adjusted net income minus amortization charges. (Free cash-flow statements also add depreciation and amortization charges back to net income to show the true earnings power of a company in a given quarter or year.)

In other words, because of the Xilinx acquisition, AMD is obliged to account for a series of expenses that do not actually involve cash leaving the company. GAAP financials account for these expenses by law, but non-GAAP reflect a more accurate reality in terms of cash flows.

As a result, GAAP financials look quite dire. But removing said expenses (non-GAAP) points to a much healthier business that it seems at first glance.

3.0 Conclusion

The odds remain favorable.

Almost ten years into my journey as an AMD shareholder, I remain optimistic about the future. The AMD-disrupting-Nvidia thesis is asymmetric. If AMD does not manage to do so to the extent it has done with Intel, for instance, the company is likely still to fare well. The demand for compute will continue increasing exponentially over the coming decade.

Having said that, the odds are favorable, at the moment, that AMD will in fact disrupt Nvidia in the coming years.

Until next time!

⚡ If you enjoyed the post, please feel free to share with friends, drop a like and leave me a comment.

You can also reach me at:

Twitter: @alc2022

LinkedIn: antoniolinaresc